Shorebird Conservation

Shorebirds are among the most imperiled bird groups globally, with many populations in the Americas experiencing sharp declines.

They are vulnerable to changes occurring across their annual lifecycles, and their conservation requires a hemispheric approach.

Shorebird Conservation

Shorebirds are among the most imperiled bird groups globally, with many populations in the Americas experiencing sharp declines.

They are vulnerable to changes occurring across their annual lifecycles, and their conservation requires a hemispheric approach.

The Midcontinent Flyway

The interior portions of Canada, USA and Mexico as well as the Coastal Plain of the Gulf of Mexico provide important stopover, wintering and breeding areas for >16.5 million shorebirds during spring migration. Sixty four percent of shorebirds using the Midcontinent Flyway of North America will migrate to interior portions of South America to spend the boreal winter. Interior habitats in South America support numerous endemic species that are of high conservation concern. North and South American shorebirds share the tundra, wetlands and grasslands with charismatic species throughout the hemisphere like polar bears, caribou, flamingos, pumas and guanacos.

photo: Christian Artuso

Vision

Partners working together with diverse human communities throughout the Midcontinent Americas Flyway to benefit shorebirds, their habitats, and humans.

Goal

By 2040, the population status of shorebirds in the Midcontinent Americas Flyway will be improved by reducing direct threats and sustaining shorebird habitats that also provide important ecosystem services and benefits to humans.

Process

Embarking on Flyway-scale conservation for shorebirds requires engaging partners and communities across the Western Hemisphere. Through a series of facilitated workshops, partners from diverse organizational backgrounds contributed their knowledge of shorebird biology, threats, habitat management, and the tapestry of human communities co-existing with shorebirds. This information was summarized in a Strategic Framework which places local action in a flyway context and facilitates collaboration at the scales necessary to conserve migratory shorebirds and their habitats.

Asociación Calidris and Manomet implementing a workshop with local communities for conservation planning at the WHSRN site Sabanas de Paz de Ariporo y Trinidad in Colombia. photo: Asociación Calidris

Geographic Scope

The Midcontinent Shorebird Conservation Initiative (MSCI) Strategic Framework focuses on the interior (i.e. central) areas of North and South America and coastal plain of the western Gulf of Mexico, defined as the Midcontinent Americas Flyway.

Pectoral Sandpiper· Shiloh Schulte

The Midcontinent Americas Flyway spans 135 degrees of latitude and across 16 countries from Arctic Canada to the steppes of Patagonia and encompasses portions of the Americas that were not addressed in the Atlantic Flyway Shorebird Initiative business plan or in the Pacific Shorebird Conservation Initiative (PSCI) strategy.

Given the size of the Midcontinent Americas Flyway, North and South America were each divided into planning units based on similarities of habitats, threats, and species present.

Arctic and Boreal: northern landscape of tundra, wetlands, and boreal forest of Canada and Alaska (excluding coastal areas already included in the Pacific Flyway). Breeding shorebirds respond to variability in wetness and shrub density across this vast region, while coastal shorelines and inland wetlands support large numbers of shorebirds during post-breeding and migration.

Great Plains: extends from northern Mexico through the central U.S to south-central Canada. Grasslands, agricultural landscapes, saline lakes, and wetlands in this region vary across gradients of precipitation, elevation, and latitude, which influences habitat use by breeding and migrant shorebirds

Mississippi Valley and Great Lakes: extends from southern Canada south, almost to the Gulf of Mexico. A diverse mix of wetlands, floodplains, and agricultural lands provide essential stopover and foraging habitat for midcontinent shorebirds during migration.

Gulf of Mexico Coastal Plain: extends in the U.S. from Alabama through Texas to Tabasco and the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico. It is the only coastal region in the Midcontinent Americas Flyway. Grasslands, agricultural lands, coastal marshes, tidal flats, beaches, brackish lagoons, and mangrove forests provide habitats for breeding, migrant, and over-wintering shorebirds.

Northern Andes: extends from western Venezuela south to northwestern Peru. Swamps, marshes, and ciénegas (spongy wetlands associated with seeps or springs) occur in the lower, northern part of the region, along with agricultural lands. Higher elevation habitats, including moist cloud forests and páramo (an ecosystem composed mainly of giant rosette plants, shrubs, and grasses) ecosystems.

South American Grasslands and Associated Wetlands: discontinuous planning unit extending from Venezuela to Argentina and includes the Orinoco Llanos and savannas of the Guianan Highlands, the Beni Savanna, the Araguaia Depression and Pantanal, portions of the Gran Chaco, and the Pampas. These landscapes share the feature of having seasonally flooded grasslands interspersed with shrublands, palm savannas, temporary and permanent wetlands, rivers, and gallery forests.

Amazon: basin of the Amazon River, stretching from the lowland forests in southwestern Venezuela and eastern Colombia to Ecuador, northern Bolivia, and Peru, almost to the mouth of the river in Brazil. Much of the region is forested, and use by migrant shorebirds is restricted mainly to wetlands and sandbars associated with the Amazon River and its tributaries.

Central-Southern Andes/Patagonian Steppe: includes the high Andes of central and southern Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina, as well as the broad, dry plains in the rain shadow of the Andes in Chile and Argentina. This region is composed of wet temperate Andean forests in the south, puna grasslands above the treeline (characterized by grasses, herbs, lichens, mosses, ferns, and shrubs), saline lakes and shrubby plains.

Grasslands in Paraguay · Photo: Andrea Ferreira

Conservation

The combination of threatened habitats, climate change, vulnerable life history, and wide-ranging migrations present significant conservation challenges for shorebirds.

Two-banded Plover

Threats

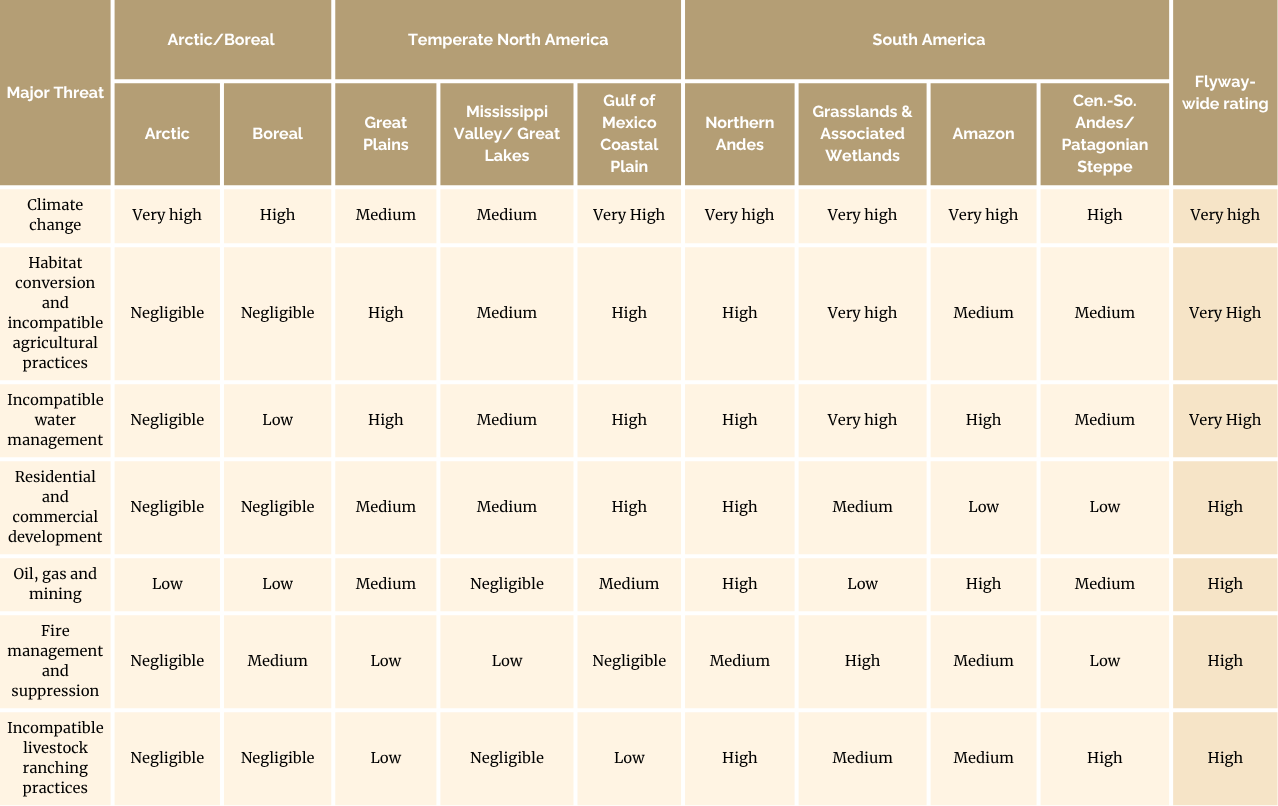

Threats were systematically evaluated at the planning unit level first, and then combined at the Flyway scale. As a result, seven major threats were identified at the Flyway scale. Threat ranking at the planning unit level are available at the bottom of the threats ranking table.

Partners and stakeholders will be able to use the framework to identify and implement the conservation, management, legislation and other local actions that meet their objectives while also contributing at the Midcontinent flyway scale.

Strategies

1. Motivate governments to increase conservation capacity

photo: Diego Luna-Quevedo

4. Manage existing and acquire new habitats

photo: Pablo Rocca

7. Integrate climate resiliency in conservation planning and implementation

photo: Luis Fernando Castillo

2. Strengthen and catalyze alliances for conservation

photo: Nathan Chinapen

5. Develop, expand and share beneficial management practices

photo: Nicolás Marchand

8. Build capacity for conservation by raising awareness and boosting education and training

photo: Laura Chamberlin

3. Increase incentives for habitat protection, enhancement and restoration

photo: Maina Handmaker

6. Improve knowledge of environmental stressors’ effects and address information gaps

photo: Juanita Fonseca

9. Sustain the Initiative’s Leadership and Actions at the Flyway Scale

photo: Diego Luna-Quevedo

Meet the Birds

Avocets and curlews, plovers and seedsnipes, phalaropes and godwits are only some of the extraordinary species that inhabit the Midcontinent Flyway.

The Midcontinent Focal species are 40 species and populations that were selected to represent the breadth of shorebird habitats and conservation needs in the Flyway. Some of these species were also selected because of conservation concern, like restricted distribution or declining populations.

The conservation of these focal species will support the conservation of all the other species within the Midcontinent Flyway.

photo: Shiloh Schulte

Baird’s Sandpiper

(Calidris bairdii)

photo: Christian Artuso

Buff-breasted Sandpiper

(Calidris subruficollis)

photo: Christian Artuso

Hudsonian Godwit

(Limosa haemastica)

photo: Christian Artuso

Lesser Yellowlegs

(Tringa flavipes)

photo: Brad Winn

Pectoral Sandpiper

(Calidris melanotos)

photo: Christian Artuso

Upland Sandpiper

(Bartramia longicauda)

photo: Christian Artuso

Wilson’s Phalarope

(Phalaropus tricolor)

photo: Monica Iglecia

Long-billed Curlew

(Numenius americanus)

photo: Tom Blandford

Marbled Godwit

(Limosa fedoa fedoa)

photo: Joel Jorgensen

Mountain Plover

(Anarhynchus montanus)

photo: Christian Artuso

Piping Plover

(Charadrius melodus circumcinctus)

photo: Christian Artuso

photo: Christian Artuso

Snowy Plover

(Anarhynchus nivosus nivosus)

photo: Joel Jorgensen

Western Sandpiper

(Calidris mauri)

photo: Brad Imhoff

Wilson’s Plover

(Anarhynchuswilsonia wilsonia)

photo: Monica Iglecia

Andean Avocet

(Recurvirostra andina)

photo: Lars Petersson

Diademed Sandpiper-Plover

(Phegornis mitchellii)

photo: Lars Petersson

Gray-breasted Seedsnipe

(Thinocorus orbignyianus)

photo: Adrian Braidotti

Magellanic Plover

(Pluvianellus socialis)

photo: Brad Winn

Rufous-bellied Seedsnipe

(Attagis gayi)

photo: Morten Ross

Tawny-throated Dotterel

(Oreopholus ruficollis)

photo: Brad Winn

Two-banded Plover

(Anarhynchus falklandicus)

Endemic South American Snipes

(9 Gallinago sp.)

photo: Jhonathan Miranda

Short-billed Dowitcher

(Limnodromus griseus)

photo: Alan Kneidel

We abuse land because we see it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.

- Aldo Leopold

Acknowledgements

Funding to develop the framework came from federal agencies in Canada as well as ConocoPhillips. Of equal value is the in-kind work from workshop participants, technical steering committees and others. This work would not have been possible without the operational and technical assistance of: Coastal Bend Bays & Estuaries Program, and Foundations of Success.